Posts Tagged ‘beatific vision’

Gurdjieff & Christianity: part one

Joseph Azize

I feel that the time has come for this blog to address the relationship between Gurdjieff, his teaching and methods on the one hand, and Christianity on the other. I have been pondering the issues for some time, but have always sensed that the issues were too big for me to tackle just now. Really, they still are, and maybe always will be. But I’ve found that the exercise of writing helps me to understand, to see where I don’t understand, where I can’t understand, and to perceive more clearly where the limitations in my thought lie. So, the fact that a topic is difficult for me, or even beyond my capacities, may be a reason to attempt it, to try to expand my range.

The impulse to broach the topic right now came from an acquaintance who asked me some pretty good questions about Gurdjieff and Christianity. Unfortunately, the information available to him is so lopsided or even distorted that he cannot even obtain a half decent idea of the possibilities of Gurdjieff’s teachings and methods. Once I addressed myself to the topic, certain very clear ideas appeared as if they’d been waiting to be articulated … and so, here we are. I’ve planned this as a series of short blogs, of no more than 1,000 words each, to present a few of my more or less tentative conclusions in crisp outline.

My first thesis is this: Gurdjieff’s teaching and Christianity have the same aim, to secure eternity with God. It seems to me to be obvious, and entirely unoriginal, to say that our lives depend upon our aim. If I have no aim, then, as Mr Adie said, everything is equal. Aim brings meaning to life and unity to our strivings. Multiple, mixed or conflicting aims lead to futility, meaninglessness and disturbance. Therefore, it is of the utmost significance that the Christian religion and Gurdjieff’s system coincide in aim.

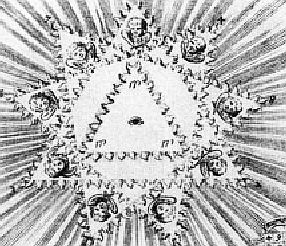

Of course, they express this one aim in their own unique terms. But if my aim accords with that of Christianity – to attain to the beatific vision – then it also accords with Gurdjieff’s, as stated in Beelzebub’s Tales to his Grandson. There he says that it is possible for one to become “a particle, though an independent one, of everything existing in the great universe” (183, see also 162, 244-5, 384 and 452). On the Planet Purgatory, he said, souls strive to purify themselves specifically to be able to unite with and become part of the universal “Greatness” (801). In the 1930 typescript, it states:

… the souls inhabiting that planet Purgatory might have a perfect and quiet existence, with everything uniquely favourable. Nevertheless, for them these external circumstances of quiet and comfort simply do not count at all. They are entirely absorbed in the increasing labour of their purgation; and only the hope of one day having the good fortune and the possibility of becoming a part of the Greatness which is fulfilled by our All-possible Endlessness for the good of All, appears occasionally to give them peace.

There is an important reference to the beatific vision, but it is characteristic of Gurdjieff that it is perhaps secondary to unity of being. That the beatific vision is the ultimate Christian aim is trite. Catechetic texts abound in statements such as the following: “Faith is the indispensable prelude to the beatific vision, the supernatural end of man. Both are immediate knowledges of God, faith the hearing of His word on earth, vision the seeing of His face in heaven. Without revelation there would be some natural knowledge of God, but not the knowledge of faith.” As we shall explore in future blogs, this idea of the necessity of revelation is found also in Gurdjieff, and his references to “messengers from above”.

Aquinas said that “the beatific vision and knowledge are to some extent above the nature of the rational soul, inasmuch as it cannot reach it of its own strength; but in another way it is in accordance with its nature, inasmuch as it is capable of it by nature, having been made to the likeness of God.”

This, it seems to me, is also a good summary of Gurdjieff’s position. We have possibilities, as Gurdjieff said, “according to law”. The most important of our possibilities do not depend on us, they are part of the makeup of creation as it is. What depends on us is that we take advantage of our lawful possibilities. That Christians will speak of “grace” whereas Gurdjieff does not is merely a semantic difference. Christians also speak of “providence” and “predestination”, although less frequently than of “grace”, and these all come down to the same thing. Calvin utterly misunderstood predestination, and since him, the Western Christian discourse has been somewhat confused. To my mind, Gurdjieff can best explain how these concepts all fit together.

“Grace” refers to the action of God (chiefly felt in the soul, but also manifested as the rare miracle), and to the divinely planned system of the creation.

“Predestination” in human terms, is pretty much like the way that the Department of Roads laid down a broad street between Rydalmere and Parramatta. But if I want to travel to the predestined end (my home in Rydalmere), I still have to drive my car. The road is there by providence: the facilitating of road-making, driving and navigating. That I do not crash or lose my way is due to grace: that God has freely given me (the etymological meaning of “grace”) the means of availing myself of this providential arrangement.

Gurdjieff says little about grace in the first sense, although it is actually in Beelzebub, e.g. the pardoning of Beelzebub. For this reason, among others, the apparent difference between Gurdjieff and Christianity is greater than it is. But as I have said, Gurdjieff shares the aim of Christianity, to bring humanity to God. And that is the most possible significant fact.

JOSEPH AZIZE has published in ancient history, law and Gurdjieff studies. His first book The Phoenician Solar Theology treated ancient Phoenician religion as possessing a spiritual depth comparative with Neoplatonism, to which it contributed through Iamblichos. The second book, “Gilgamesh and the World of Assyria”, was jointly edited with Noel Weeks. It includes his article arguing that the Carthaginians did not practice child sacrifice.

The third book, George Mountford Adie: A Gurdjieff Pupil in Australia represents his attempt to present his teacher (a direct pupil of Gurdjieff and Ouspensky) to an international audience.The fourth book, edited and written with Peter El Khouri and Ed Finnane, is a new edition of Britts Civil Precedents. He recommends it to anyone planning to bring proceedings in an Australian court of law.

“Maronites” is pp.279-282 of “The Encyclopedia of Religion in Australia” published by Cambridge University Press and edited by James Jupp.

=============================